.

Royal Air Force, Pembroke Dock

The Royal Air Force’s arrival in 1930 brought hope to a community still reeling from

the closure of the Royal Dockyard four years earlier. The sheltered Haven waters

were ideal for the operation of flying-boats and the newly formed No 210 Squadron

flew here in June, 1931. Their Supermarine Southampton's – and later Short

Rangoon's and Singapore IIIs - were an ever-present part of Pembroke Dock’s daily

life in the 1930s.

During World War II Pembroke Dock became one of the most important stations in

waging the Battle of the Atlantic and the ceaseless war against the German U-Boat.

At one time in 1943 no less than 99 flying-boats – Sunderland's and Catalinas – were

at Pembroke Dock, making this the largest operational station in the world.

From Pembroke Dock many RAF and Allied squadrons operated at various times.

Men of many nations flew from the Haven, their patrols taking them far out into the

Atlantic, deep into the Bay of Biscay, above the Western Approaches and, as part of

the D-Day operations, protecting the sea lanes leading to the Normandy Invasion

beachheads.

Known simply as ‘PD’ to all involved with flying-boats, the Pembroke Dock

community took the airmen to their hearts and a second posting to the air station

was always welcomed.

Backing up the ‘front line’ activity of the squadrons was a substantial maintenance

base, a large Marine Craft Section with many and varied craft and a sizeable WAAF

contingent, the first of which arrived at the end of 1939.

Post-war, ‘PD’ continued as an RAF station (201 and 230 Squadrons) until the

Sunderland's were retired from home waters in 1957.

Today, the two unique flying-boat hangars still dominate the former RAF station but

the slipway used to bring flying-boats ashore was demolished to make way for the

new port facilities. The fine 1930s-style Officers’ Mess was knocked down in the

1980s but the former Sergeants’ Mess – located just inside the main gate – was

converted into a hotel.

Short Sunderland V of 201 Squadron. For allied merchant ships,

patrolling Sunderland's were friendly, protective giants. Against enemy

submarines, they were formidable adversaries.

(Imperial War Museum)

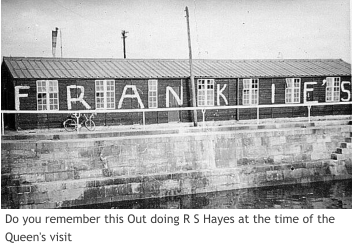

Empire Air Days attracted thousands of spectators to

the Dockyard in the 1930s. Like earlier ship

launchings, they offered a chance to view the

wonders of military technology at close quarters.

Here, visitors step aboard a

Singapore III flying boat.

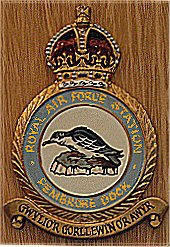

The Welsh text expresses the purpose of RAF Pembroke

Dock-"Watching the west from the air."

Note: "The RAF Pembroke Dock homepage", at http://www.geocities.com/aj_p_joyce/ includes "RAF marine craft homepage", and material on 1109 MCU. Mr John Joyce was stationed in PD from

1955, and maintains "service pals", "memories" and "roll call" sections. These offer recollections of the RAF station and town at that time.

Pictures by courtesy of : Sunderland, Imperial War Museum ( * please note: this image may not be copied without the permission of the Imperial War Museum) - badge: Pembroke Dock Museum Trust

(photograph: Creative Looks) - Empire Air Day, Mr R. Ridley.

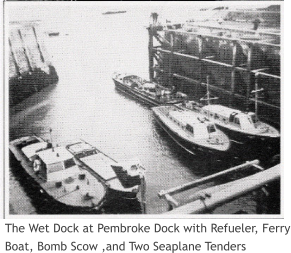

Royal Air Force Pembroke Dock-Marine Craft Section

The 1932 Marine Craft Section

In these pages we are endeavouring to make a History of the

Marine Craft Section Pembroke Dock from the time it started in

1930 up to its close in 1959. Pembroke Dock became the

largest flying boat station in the world and the Marine Craft

section was one of the main lynch pins. We aim to show those

who served there, the launches used and any events that took

place over that period of time with photographs and text. Any

information or pictures that can help with the building of this

important section of history would be gratefully appreciated.

More information can be found at

http://rafmarinecraft.bravehost.com/index.html

Royal Air Force Pembroke Dock Marine Craft Section/Ground Crew

Squadron Leader Morse, Commanding Officer

Squadron Leader Garwood, Commanding Officer

Flight Sergeant Fauchan

Flight Sergeant Mears

Sergeant Delpech now Sir Robert Delpech

Sergeant Hutton

Corporal Paddy Batt

Corporal Sammy Hall

SAC Nobby Clarke

SAC Toney Le Britten

SAC Brin Rixon

SAC Jim Berry

SAC Cider Elford

Disbandment of Unit signal Click to view

Demolition of the Old Marine Craft Billet.

Royal Air Force Pembroke Dock Ground Crew Association Newsletter

35 2005

van Southall's book "They shall not pass unseen" tells the story of 461 Squadron RAAF in World War II. The author served as a Pilot Officer in the squadron.

We read of confrontations with the enemy and - in the extract below - with the elements.

The weather which was winter began to close in over the Atlantic. ‘Winter was as great an enemy as the German, because the weather was there when

the German wasn’t. When the fighter aircraft retired to their bases and the fighter pilots put their feet up to the stove, the Sunderland crews still went out

into conditions which frightened them. They still had to look for the U-boat whether the U-boat was there or not. When their eyes were useless they used

radar. They’d fly out blind and come back weary and - shaken. They’d nose for hour after hour through unending storm-clouds chilled to the marrow

watching the eerie blue flames of St Elmo’s fire playing round the engines and the guns and the aerials, entrusting their lives to the skills of their captain

and navigator.

Buls was one who disappeared into weather like that. Continuous rain, low cloud, electrical disturbances, hail and snow smothered the Bay of Biscay. Buls

flew into it all and vanished. They heard his SOS but never found him. They looked for him for two days, eleven aircraft in all. Two of them crashed trying

to find their bases when they came off patrol, but the raging seas, the storm and the snow held onto the secret of Buls and never gave it up.

Biscay’s skies were never less than temperamental. Wild beauty, brilliant sunshine and savagery could engulf a man in consecutive minutes. Clear skies

were suddenly black with the thunderous assault of hail. Storm-clouds melted into sunlight. The gloom of rain became cold light-rays and shadows,

sometimes even became a rainbow ring, Irish magic, completely encircling and flying with the aircraft, a spectacle of incredible beauty, of unforgettable

mystery, vanishing as suddenly and as strangely as it had come.

Weather and morale were inseparable. Against the Hun man encountered man. Against the elements he was a child in a lion’s den. The bravest of them

dreaded the cold furies of an Atlantic gale. The Sunderland, despite its size, was tossed like a toy. The pilots could have sought smoother air higher up, but

discipline and self-respect forbade it. One didn’t hunt for U-boats at a height of ten thousand feet above the weather. One hunted for U-boats underneath

the cloud-base in the

weather, unless the cloud touched the sea. The anti-U-boat patrol or the convoy escort then became an inhumanly sustained test of endurance, and out of

such ordeals came stories like this one. In such weather the incredible sometimes happened. They make the strange stories one relates with embellishment

to wide-eyed grandchildren. Yet there are times when the tale needs no embellishment, because truth is stranger than fiction, and truth, run amok,

beggars the powers of invention.

Steaming in along the Western Approaches was a convoy looking for air escort, so a Sunderland was sent out to meet it. .....

It was Manger’s ... Fred was a serious type and he had a lot to be serious about. He was a natural for leg-pulling. He was made for it. He used to stand in

the mess, long and lean, and take it all with a wide grin and a slow and serious shake of his head.

So Manger went out to meet the convoy and the weather was violent. The sky was cloud and nothing else. For four hundred miles south-westward from

the Scilly Isles, those little jewels which cluster at the toe of England, the cloud didn’t break once.

They didn’t see the ocean for a moment; Navigator Kennedy never had the chance to check his winds or his track; they just thundered on through a wet

gloom which seemed eternal. Met. reports said the cloud reached up from the surface of the sea to a height of thirty thousand feet over an area which was

so huge its actual limits were unknown. It’s difficult now to comprehend why the aircraft was sent out at all.

The progress of the Sunderland was slow and incredibly rough, but it flew on farther and farther into the south-west at five thousand feet, quite blind,

unseeing, almost entirely unaware of the true nature of its surroundings. It was impossible for airmen to observe what lay ahead when they couldn’t see a

yard beyond the wing-tips. They couldn’t avoid the more savage storm-zones if they didn’t know they were there. They couldn’t sense by smell or feel the

boiling monster which now lay directly on their course, so they flew towards it when a pilot with eyes would have turned and run for his life.

There are clouds and clouds. Most are harmless, a few are death-chambers. Sometimes a cumulo-nimbus cloud builds up to a volume of violence

impossible to measure. Sometimes they rise in funnels to tremendous heights. Sometimes they’re packed with fantastic air currents, hail and ice and

electricity. They can tear an aircraft to pieces. They’re avoided like the plague. Manger’s Sunderland flew on towards one, towards that weird and

wonderful cloud. Manger had gone down to the galley for a while and Shears and Davenport were left on the bridge to fly the aircraft. Shears and

Davenport were not particularly happy. Neither was Manger although he wouldn’t have said so, but he’d got away from the wheel for a break to stretch his

limbs and relax just a little, as much as any captain could relax while he was airborne.

Drinks went up to the bridge — tea and cocoa and beef extracts. Each man preferred something different and usually got what he asked for. A hot drink

was a good friend to have around, but Shears couldn’t get his down; couldn’t keep his hands away from the controls long enough to drink it. They were

beginning to worry him those controls, because they were alive in his hands. For two minutes the air had been growing rougher and rougher and the needles

of the instrument dials were becoming frantic. Manger, still down in the galley supervising the distribution of the drinks, couldn’t see the instruments, but

he knew what was going on because he had to hold to a spar to stand upright. There wasn't a man down below who could stand. They all hung to spars and

stringers and bulkheads and hung on hard. Manger wanted to take the wheel again, but there were some things a captain didn’t do. He didn’t take the

wheel away from a pilot unless enemy fighters were sighted or a U-boat was coming up ahead. He had to have confidence in his pilots, and his pilots liked

him to have that confidence. But this was different, because when things became abnormal the responsibility became even more the captain’s. Manger

decided to go up to the bridge and say “I’ll give you a spell. This is pretty rough. It’s very tiring.” But he didn’t get there for a moment because suddenly

the Sunderland shook as though it had struck a brick wall. Its nose flicked up and the engines screamed and she went straight up vertically at a gathering

speed, although forward speed fell away to almost nothing. Shears and Davenport fought the aircraft with a united effort. They jammed the control

column fully forward but the boat still went up, higher and higher, and nothing could stop it.

Manger fought his way up the companionway like a man demented. How he got to the bridge heaven alone knows, but he lifted Shears bodily out of the

seat and threw himself at the wheel.

The Sunderland still went up and Manger was powerless. He couldn’t get the nose down. There was nothing on the control surfaces because the aircraft

was in a state of stall, shuddering and shaking violently, yet still going up at an unbelievable speed. It turned on its back, right over, engines spluttering and

coughing, its huge mainplane trembling like a flimsy leaf.

Instantly Manger was shot to the perspex canopy above him. He didn’t let go of the controls. He hung onto them, but he was standing on his head.

Shears floated off the deck and drifted up to the roof. He had the amazing presence of mind to feel for the throttle levers with his feet and kick them

wide open.

Kennedy, fiercely clutching his nav. table, was a strong man, but not strong enough to stay on deck. The table broke in his bands and he went up and

came to rest in an ungainly heap in the astrodome and received a flood of charts and instruments in his lap.

Evans, tail gunner, was thrown against his reflector sight and knocked unconscious. Lids came off the ammunition pans and belts of bullets wove through

the turret.

The cook, down in the galley, rose to the roof to meet it in a natural sitting position. He looked up to the floor, and the meal he had so patiently prepared

came towards him in odd pieces. The saucepans and a kettle floated in mid air. Next door, in the ward-room, the bunks swung open. Half a dozen

parachutes drifted out, strangely burst their packs and swamped the deck with silk. Bird, the wireless operator, ascended from his transmitter and,

suspended like a spaceman, reached down and keyed an SOS.

Then the great tumbling column of air was gone. The flying-boat seemed to fall over the edge and it righted itself and the crewmen came raining down

from the roof in all attitudes, from one end of the aircraft to the other. Manger quickly mastered the controls, got the Sunderland straight and level, found

his breath, and switched on his microphone.

“The weather’s bad,” he said, “but it’s not going to get worse. That was a cu-nim cloud in case you want to know. I’d like a report from everyone. Let

me hear how you are. . . . Navigator—I think we’ll have a course for home! And Engineer—make an immediate inspection of the air-craft and report damage

to me!”

There was damage in plenty. The aircraft presented a remarkable picture of disorder. The decks were littered with debris. It was difficult to credit that so

much had been stored so neatly throughout the aircraft. Pyrotechnics, safety equipment, ammunition, instruments, papers, maps, parachutes, pencils,

cups, plates, knives, forks and personal odds and ends were heaped in hopeless confusion — but the pots and the pans and the dinner had vanished. Later

they were found beneath the floorboards.

On the bridge spilt battery acid was eating into the control cables and had to be neutralized. Engine mounts were buckled and one engine had moved a

quarter of an inch along the wing. A ladder at the rear had stuck in the cables for the elevators and rudder, yet hadn’t jammed them. A small wireless

receiver had risen from the lower deck into the bomb-rack overhead and remained wedged among the depth-charges. The rear gunner regained

consciousness and marvelled to find that he had knocked the reflector sight from its bracket with his head, an operation normally requiring the weight of a

hammer — and Shears - Shears reached under the captain’s seat for his cup of tea. Before the aircraft had turned over he’d put it there because he’d been

too busy to think of it. When he picked the cup up again it wasn’t empty.

The wireless operator introduced further interest. “W.T. to Captain,” Bird said. “Group has instructed us to land at Gibraltar.”

‘Is that all?” “Yes!” “Navigator to Captain,” growled Kennedy. “We couldn’t make Gibraltar if they offered a bonus. What do ... they propose

we use for fuel?” So they went home.

Text and photograph reproduced by courtesy of Mr Ivan Southall.

Dangerous Cloud

Ivan Southall

The author and his crew at RAF Pembroke Dock

during World War II. Click picture to view

Back row : "Jock" Rentoul, Bob Norris, Jack

Kendall, John Eshelby,

Keith Stevenson, Bob Hobbs. Front row : Reg

Player, Norm Wyeth,

Ivan Southall, Jack Wylie, Paul Pfeiffer.

Pembroke Dock has more than two hundred years of well recorded military heritage that stretches even further back to Henry Tudor’s invasion of

1485. The aim of the Pembroke Dock Sunderland Trust is to share this unique history and experience with the world using a fine Georgian building,

the Royal Dockyard ‘Garrison Chapel’, to create the Pembroke Dock Heritage Centre.

Pembroke Dock once had a thriving shipbuilding industry, c1785, building more than 250 ships and sea craft including all five of the Royal Yachts

that preceded Britannia. Very few people are aware of this substantial maritime heritage though much of the man made landscape confirms the

activity.

Pembroke Dock was the world’s largest ever Flying Boat port and is unique in that it is the only town within the UK that had an association with all

three UK Armed services – the Royal Navy, the Army and the Royal Air Force at the same point in history.

Background to the Sunderland Trust Project

Read More

119 Squadron, Royal Air

Force

June 1941 – April 1942

Sunderland's

201 Squadron, Royal Air

Force

March – November 1944

January 1949 – February

1957

Sunderland's.

209 Squadron, Royal Air Force

July– December 1940

Catalina's.

210 Squadron, Royal Air Force

Home station between June 1931

and July 1940

October 1942 to April 1943

1939-40 : Southampton's,

Rangoon's, Singapore III s and

Sunderland's.

1942-3 : Catalina's.

228 Squadron, Royal Air Force

Principal home station between

December 1936 and June 1940

May 1943 to June 1945

1936-40 : Stranraer's and

Sunderland's.

1943-45 : Sunderland's.

230 Squadron, Royal Air Force

December 1934 - September 1935

September-October 1936

A short period in 1946

February 1949 – February 1957

1923-36 : Singapore III s

1946, 49-57 : Sunderland's.

240 Squadron, Royal Air Force

May – July 1940

Catalina's.

320 Squadron, Royal Air Force

Dutch unit. June – October

1940

Fokker T-VIII-W floatplanes.

321 Squadron, Royal Air Force

Dutch unit. June 1940

No aircraft; formed here only,

then to Carew Cheriton.

0 Squadron, Royal Australian

Air Force

September 1939 – January

1940, also in 1941

Mainly Australian manned.

Sunderland's.

461 Squadron, Royal Australian

Air Force

April 1943 – June 1945.

Mainly Australian manned.

Sunderland's.

422 Squadron, Royal

Canadian Air Force

November 1944 – June 1945.

Mainly Canadian manned.

Sunderland's.

VP-63, United States Navy

May – November 1943

(First US Navy squadron to

operate in European Theatre)

PBY-5 Catalina's. (First US

Navy squadron to operate in

European Theatre.

308 Ferry Training Unit

Ferry training unit. 1943-44.

Pictures by courtesy of: badges from RAF memorial window, reproduction in Pembroke Dock Library, Flying Boat Reunion Committee - 230 Squadron badge, Imperial Tobacco (originally

a Player's cigarette card).

Squadrons / Units based at Pembroke Dock

TOP

HOME

R.A.F. Donated Personnel

Information (New 2018)

Thought you might add to your

information on people serving

at Pembroke Dock – Corporal

Robert Fritz Delpech married

Marjorie Cadogan on 7

February, 1953 at St Mary’s

Catholic Church, Pembroke. His

RAF number was 4024257 and

he was a Corporal at the time.

Hope this is of interest. I would

like to know which one is

Sergeant Delpech in the photos

shown on the site and his duties

etc. Just trying to fill in details

of the Cadogan family. (John

Mumford August 2017)

personnel

(Amendment, updates and additions) (AJ) Anndra Johnstone

This site is designed, published and hosted by CatsWebCom Community Services © 2018 part of Pembroke Dock Web Project